Arthur Machen and the Horror of Harlesden (Part 2)

Reprinted, with minor variations, from The Willesden Local History Society Journal, No. 34, winter 2011/12

Last time we saw that the Welsh fantasy writer Arthur Machen (pronounced so as to rhyme with ‘bracken’) wrote a very derogatory description of Harlesden in his short story, The Inmost Light. Why did Machen dislike Harlesden so much? Machen wrote three volumes of autobiography, Far Off Things (1922), Things Near and Far (1923) and The London Adventure (1924), though this last was really just a book of musings on London rather than a genuine autobiography. Far Off Things provides the answers.

In 1883 the young Machen was living in a room at 23 Clarendon Road, Notting Hill (the street address comes from Things Near and Far.) He was poor, “all alone in my little room, friendless, desolate” and subsisting on a diet of dried bread and green tea. Despite having spent a lonely childhood, the lack of human contact clearly depressed him deeply, and he missed the countryside. So, “as the spring of 1883 advanced, and the weather improved and the evenings lengthened, I began the habit of rambling abroad in the hope of finding something that could be called country. I would sometimes pursue Clarendon Road northward and get into all sorts of regions of which I never had any clear notion.”

These rambles led him to the Harrow Road and into what is now Brent. Being used only to country churchyards, and having never seen an urban necropolis, he was horrified by Kensal Green Cemetery, which he calls “the goblin city”, a terrible place of “white gravestones and shattered marble pillars and granite urns, and every sort of horrid heathenry.”

On these walks, Machen discovered what would nowadays be called the ‘urban fringe’, the usually rather grotty transition zone where city and country meet:

“I would pass that sad zone of destruction and disgrace that always lies just beyond the furthest points of the suburb. These are the places where the hedges are half ruined, half remaining, where the little winding brook is defiled, but not yet a drain, where one tree lies felled and withered, while its fellow is still all green. Here curbstones impinge on the fields, and show where new, rabid streets are to rush up the sweet hillside and capture it; here the well under the thorn is choked with a cartload of cheap bricks lately deposited. I would pass over these dismal regions and come, as I thought, into the fair open country, and then suddenly at the turn of the lane I would be confronted by red ranks of brand-new villas: this might be Harlesden or the outposts of Willesden.”

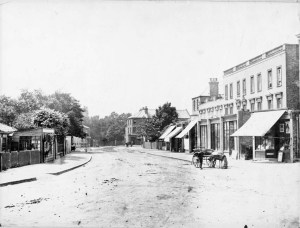

Harlesden, c. 1875

Harlesden made a particularly bad impression on Machen, as he tried to get away from the city into the green fields beyond:

“I think that on the especial occasion that I have in mind the red row of houses must have been some portion or fragment of Harlesden. I remember that, like the cemetery, this impressed me as a wholly new and unforeseen horror, something as strange and terrible as the apparition of a rattlesnake or a boa-constrictor … I had never lived in a world that might have prepared me for such things; in Gwent—in my day, at all events—there was no such phenomenon as this sudden and violent irruption of red brick in the midst of a green field; and thus when I came round the corner of a peaceful lane and saw in the midst of elms and meadows this staring spectacle, I was … aghast … I made the horrid apparition of the crude new houses in the midst of green pastures the seed of my tale, The Inmost Light … the man in my story, resting in green fields, looked up and saw a face that chilled his blood gazing at him from the back of one of those red houses that once had frightened me, when I was a sorry lad of twenty, wandering about the verges of London. The doctor of my tale lived in Harlesden … if I could have ‘translated’ the Horror of Harlesden competently I should have been a man of genius.”

It should be added that, at one point in the early 1880s, Machen briefly worked in a publishing company in Chandos Street, off the Strand, producing a calendar of Shakespeare quotations. It is in this context that he first mentions Harlesden. The firm employed three other “very cheerful and kindly young fellows of about my own age.” One of these young men married and set himself up as a stationer in Harlesden, but then sadly died soon afterwards. When Machen learnt this, it must have further jaundiced his view of Harlesden, unless, of course, he was not sure of the name of the suburb the young man had moved to and chose to make it Harlesden in his memoirs as Harlesden, to him, was such an ill-omened place.

Despite his loneliness and poverty, Machen would later envy the freedom he had experienced in the early ‘80s, contrasting it with the humiliating drudgery of working for The Evening News. Machen never lived in Brent. In 1929 he moved to ‘Lynwood’, High Street, Amersham, Buckinghamshire, where he apparently held regular court at the ‘Crown’. He died on 15th December 1947 and is buried in St. Mary’s churchyard, Amersham.

Arthur Machen’s grave in Amersham, photographed by the author

Posted (and written by) Malcolm

http://www.arthurmachen.org.uk/

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/booksblog/2009/sep/29/arthur-machen-tartarus-press

Pingback: Arthur Machen and the Horror of Harlesden (Part 1) |

Hello there, I was just wondering if you knew where that picture of Harlesden was taken? I’m a local teacher and was hoping to use the picture as part of a lesson, but I can’t place the picture in a modern Harlesden!! Thank you!